Traveling for medical treatment has been a long-standing motivation for travel since ancient times. One of the destinations that attracted such travelers were the healing centers located in Egyptian temples. The skilled ancient Egyptian physicians gained a remarkable reputation among patients from other ancient civilizations. People from both Egypt and foreign lands would journey to these medical centers, staying for a night or longer in search of cures through medical treatments or divine messages received in dreams. Architectural evidence supports the existence of these healing centers in the temples, with the sanatorium within the Hathor temple at Dendera in Upper Egypt being the only preserved example.

From a modern tourism perspective, these travels can be considered a form of tourism. This paper aims to explore the early instances of medical tourism through textual, pictorial, and architectural evidence while also applying the concepts and components of present-day tourism to the journeys undertaken by ancient Egyptian and foreign patients.

In ancient times, patients in Egypt would travel to specific destinations to seek healthcare. This tradition dates back to the earliest beginnings of medicine in ancient Egypt. Manetho, an Egyptian historian from the third century BC, noted that Athothis “Djer,” the third pharaoh of the first dynasty in the fourth millennium BC, was a skilled physician Over time, the practice of medicine in ancient Egypt developed to such an extent that Egyptian doctors gained a great reputation both within and outside of Egypt.

This advanced medical practice astounded Greek writers and travelers. In Homer’s Odyssey, Egypt is described as a land where the soil yields abundant medicinal plants, both beneficial and harmful, and where every person is knowledgeable in medicine and surpasses others in their understanding. Herodotus was particularly impressed by the specialized expertise of Egyptian physicians. He observed that medicine was divided among them, with each physician specializing in a specific disease rather than treating multiple ailments. There were eye doctors, head healers, dental specialists, stomach experts, and even those who dealt with invisible illnesses. Despite the long history of Egyptian medicine, its greatness…

The origin and reputation of its division’s growth and the precise location where Egyptian doctors were educated remain uncertain. And

practiced their medical expertise. The commonly proposed site is the temple, or more specifically,

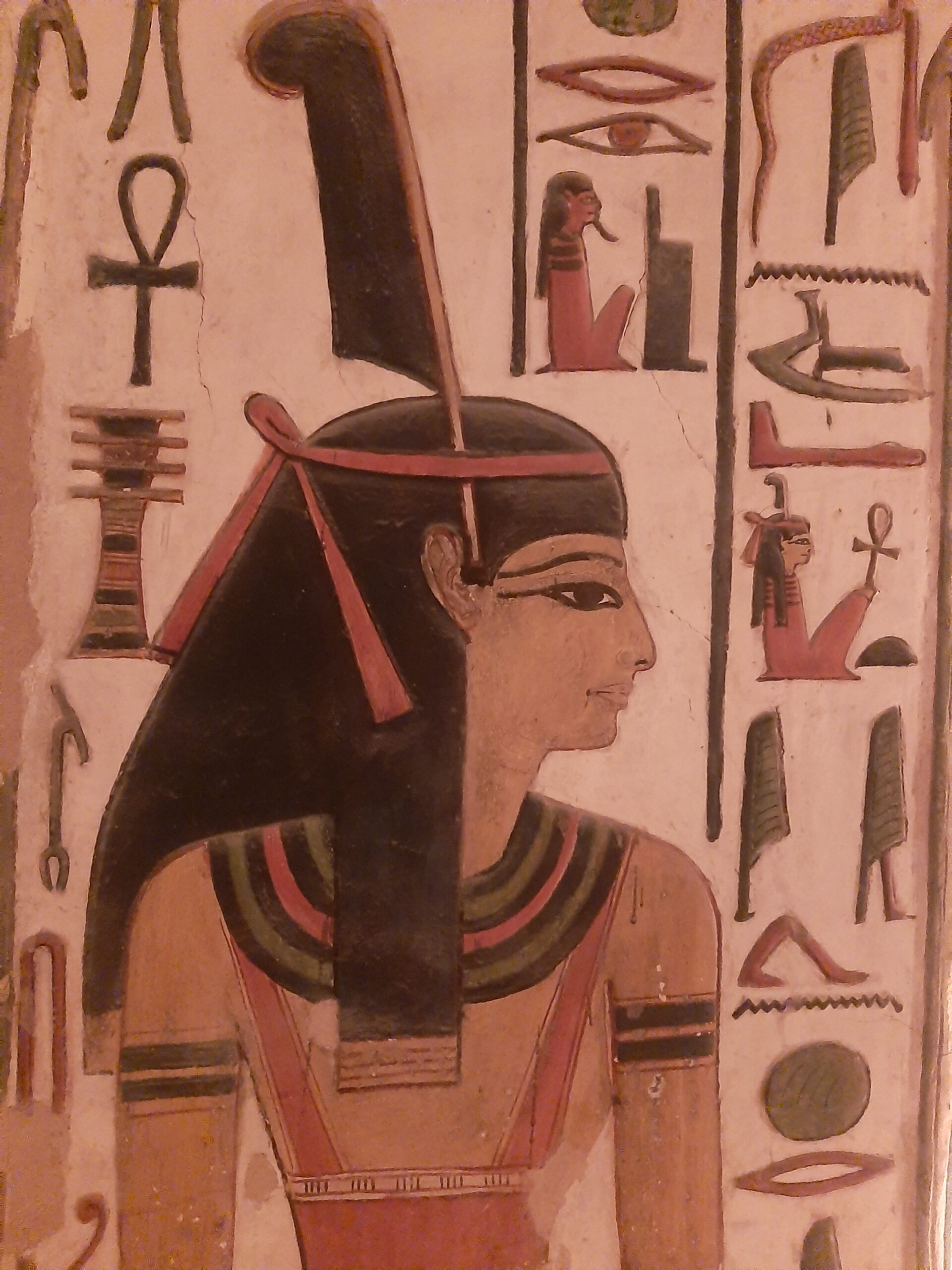

the adjacent house of life. Certain Egyptian temples served as havens for patients who journeyed there in search of medical treatment.

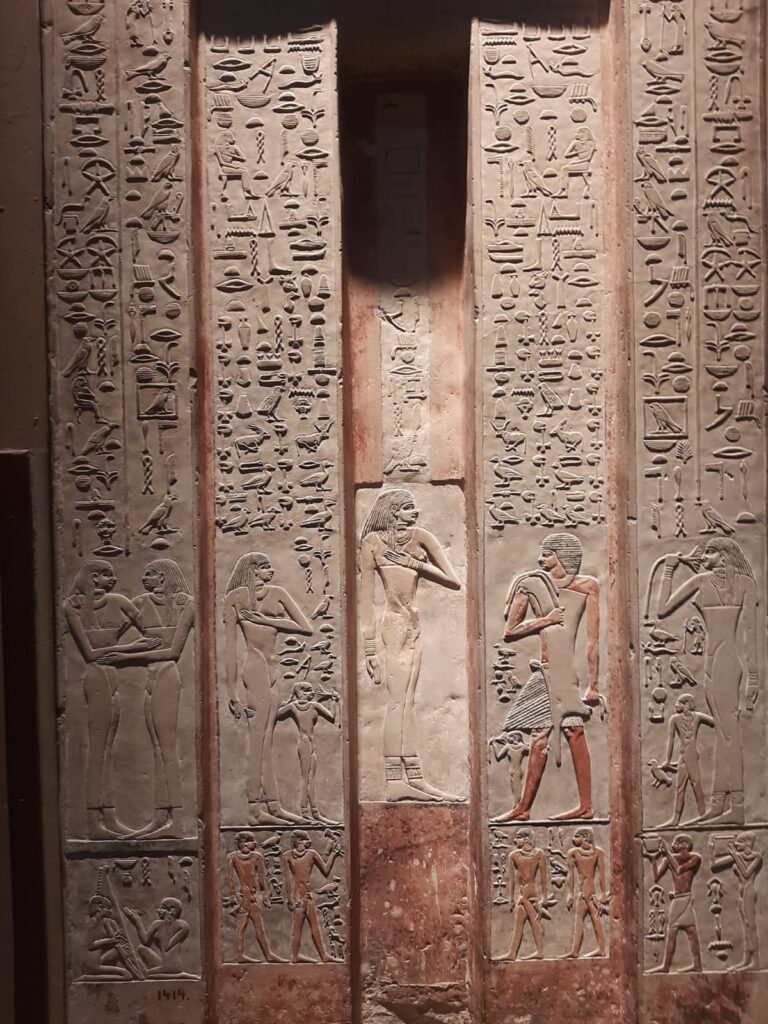

The search for textual evidence aims to establish four key points: the presence of a house of life in temples, the connection between the house of life and medicine, the role of temples as medical centers, and the travel of patients to these centers. There is ample evidence supporting the existence of a house of life in various Egyptian temples. For example, an inscription on the discovered door of Irwy in Bubastis, Eastern Egypt, from the twentieth dynasty mentions the offering made by the king to Atum, the lord of the house of life. It also identifies Irwy as the chief priest of Sekhmet. The connection between medicine and the priesthood of Sekhmet is evident in the texts of medical papyri.

Another piece of evidence for the existence of a medical education center in Bubastis is the statue of the chief priest of Sekhmet, who was the son of the chief physician Amenhotep. In Sais, located in the Western Delta, during Persian rule, Udjahorresnet, the chief physician and chief priest of the goddess Neith, left a lengthy text on his statue. He mentions the instructions given to him by the Persian king Darius to restore the house of life in Sais. Udjahorresnet states that he provided the house of life with students, teachers, and tools to treat every patient. He also highlights that Darius emphasized the value of medical art. In Abydos, situated in Upper Egypt, the overseer of the Neith temple, Peftjawaneith, from the twenty-sixth dynasty, recorded on his statue, now preserved in the Louvre, that he restored the house of life after its collapse. It is important to note that both Udjahorresnet and Peftjawaneith were physicians and priests of Neith. These restoration works were carried out by priests who also practiced medicine.

There is evidence to suggest the existence of medical educational centers within temples, dating back to earlier times. The Ebers Medical Papyrus, authored by an individual who gained wisdom from the gods of Heliopolis and Sais, mentions how they provided protection and taught him the art of healing various diseases. This notion is further supported by the Hearst papyrus. These texts indicate the presence of a medical education center affiliated with the temple of Atum in Heliopolis, located in Lower Egypt. Such evidence confirms the existence of “houses of life” in numerous Egyptian temples, which were likely associated with the teaching and practice of medicine. While there were no specific schools dedicated solely to medical education, it is highly probable that medical knowledge, like other forms of knowledge, was imparted within the temple premises. The House of Life likely had a dedicated section for teaching medicine. The connection between the House of Life and medicine is supported by various references, such as physicians holding titles related to the House of Life. For instance, Niankhre, a physician in the fifth dynasty, served as the chief of the house of life. Aha, the chief scribe in the House of Life, also held the position of chief of the myrrh house, which was closely associated with medicine and frequently mentioned in medical prescriptions. Similarly, Menna, a physician in the eighteenth dynasty, held the title of “the chief physician in the house of life.” These examples provide clear evidence of the link between the house of life and the practice of medicine. Additionally, archaeological findings in the ruins of the house of life in the city of Akhetaten have uncovered medical instruments, further supporting this connection.

Houses of Life

This suggests that the building had a medical purpose. When Bentresh, the sister of Neferure, the wife of Ramses II, fell ill, a messenger was sent to Egypt to seek medical assistance for the princess. The pharaoh then dispatched one of the scientists from the House of Life to provide aid. These references imply that the houses of life associated with Egyptian temples served some medical functions and offered healing services. While there is no definitive proof that temples were used as medical centers, there are indications to support this claim. These indications include the presence of houses of life connected to the temples, except for Amarna, where they were separate. These houses of life served as educational centers for teaching medicine. Additionally, the discovery of medical papyri near temples, such as the Ramesseum papyrus found in a wooden box beneath the brick magazine behind the great temple of Ramesseum, provides further evidence. Furthermore, the titles held by temple physicians, such as the physician Pahatyu of the New Kingdom, who was titled “overseer of the physicians in the temple of Amon,” and Amenhotep, a physician of the nineteenth dynasty, who held the title of “chief physician in the temple of Amon,” indicate the existence of medical practices within the temples. Nakhtsaes, a physician from the Late Period, held the title of “overseer of doctors in the temple of Ptah.” This last title suggests that the position required skill and knowledge rather than relying on magic.

The text of Udjah-arr, which mentions the provision of healing tools in the house of life to treat every patient, serves as a significant reference to the practice of medicine in the temple of Neith in Sais. As for the travel of patients to these supposed healing centers in Egyptian temples, There is textual evidence left by these patients on the walls of the temples. Along the walls of a small cave high above the temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, these inscriptions can be found.

Nebwa, a priest and scribe of the memorial temple of Tuthmosis I, mentioned that “he came to be cured completely,” which suggests the existence of a sanatorium at Deir el-Bahari in the New Kingdom. However, it is possible that the correct interpretation of the text is “he came to see this place and to enjoy himself in it” or “to have a good time.” The pleasures available in this remote area are not entirely clear, aside from the tranquility it offers. Nebwa may have stumbled upon it while visiting the Deir el-Bahari temples and took advantage of the opportunity to find some cool shade or perhaps indulge in some refreshments. An intriguing story has survived, illustrating a visit to the temple of Imhotep, the Egyptian god of medicine, to practice incubation. The story revolves around a man named Satmi Khamuas, the son of Pharaoh Usermares. He was deeply troubled by his inability to father a son with his wife, Mahftuaskhit. One day, when he was particularly despondent, his wife, Mahituaskhit, went to the temple of Imhotep, son of Ptah, and prayed before him. She pleaded for his attention and asked for his help in conceiving a male child. Afterward, she slept in the temple and had a dream that same night. In her dream, a voice advised her to seek a remedy for her infertility from the god himself by going to her husband’s bathroom and taking the leaves of Colocasia growing there. She was instructed to use these leaves to create a remedy and give it to her husband, and then to lie by his side. The voice promised her that she would conceive that very night. When Mahituaskhit woke up from her dream, she followed the instructions exactly as she had been told. She lay by the side of her husband, Satmi, and indeed conceived a child. As time passed, she began to show signs of pregnancy, and Satmi joyfully informed Pharaoh. An amulet was placed on Mahituaskhit, and a spell was recited over her. Eventually, she gave birth to a healthy child.

A well-known stele from the Ptolemaic Period, currently housed in the British Museum, recounts a similar tale of Imhotep. He performed numerous miracles in Egypt. This particular story revolves around a woman named Thet-Imhotep, who was married to the priest P-Shere-en-Ptah at the age of fourteen during the ninth year of Ptolemy XIII’s reign. Over the course of twelve years, she gave birth to three daughters but was unable to conceive a son, which greatly saddened her husband. In their desperation, both Thet-Imhotep and her husband prayed to the god Imhotep, who was the son of Ptah, for a son. In a dream, the god appeared to P-Shere-en-Ptah and promised to grant their wish if certain tasks were carried out in connection with the temple. Upon awakening, the priest immediately initiated the required works, and shortly after their completion, Thet-Imhotep gave birth to a son named Imhotep, also known as Pedi-Bast.

Furthermore, historical records indicate that Egyptian physicians, often referred to as “learned men” or “knowers of things,”. He would travel to foreign lands to treat patients. These accounts date back to the late eighteenth Dynasty and continue into the Late Period. Foreign kings and princes frequently sought the expertise of Egyptian physicians. And they were even dispatched by Egyptian kings themselves. For instance, there are Akkadian records that reveal the regular practice of sending Egyptian doctors to Hatti. That was during the reign of Ramesses II. One notable physician, Paraemhat, made multiple journeys to Hatti. He provides medical assistance to both Hattusilis III at the Hittite court and his vassals.

Sleep Temples

The sleep temples served as places for both healing and personal growth. Individuals would be led to a darkened chamber where they could sleep and receive treatment for their particular ailment. The treatment process included chanting, inducing a trance-like or hypnotic state, and analyzing the patient’s dreams to determine the appropriate course of action. Additionally, practices such as meditation, fasting, baths, and offerings to the patron deity or other spirits were commonly incorporated.

These sanctuaries were established by the priests of Imhotep. He was the god associated with wisdom and medicine. Positioned near sacred locations. These temples were intentionally designed to create a serene and peaceful atmosphere, fostering relaxation and tranquility.